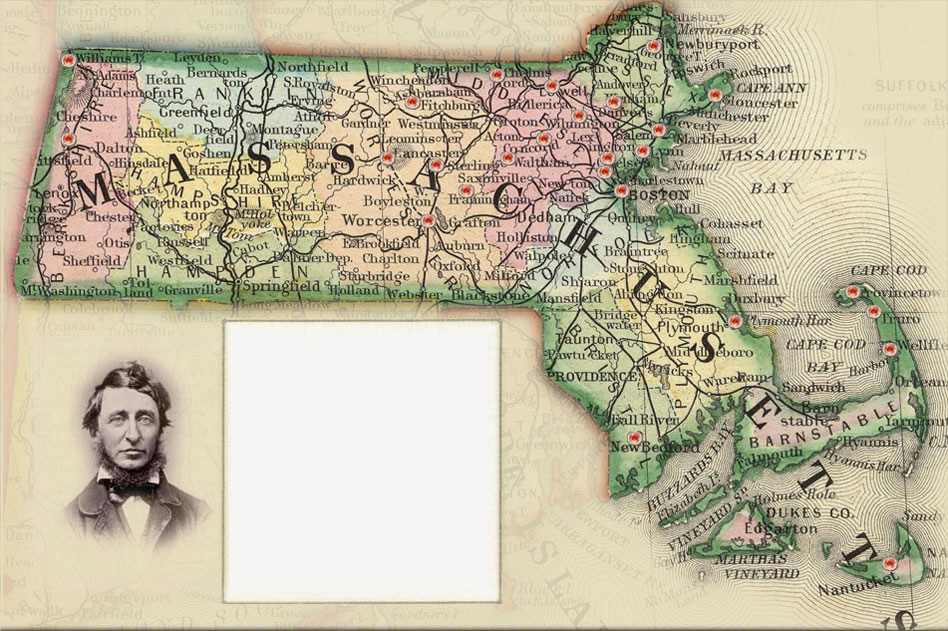

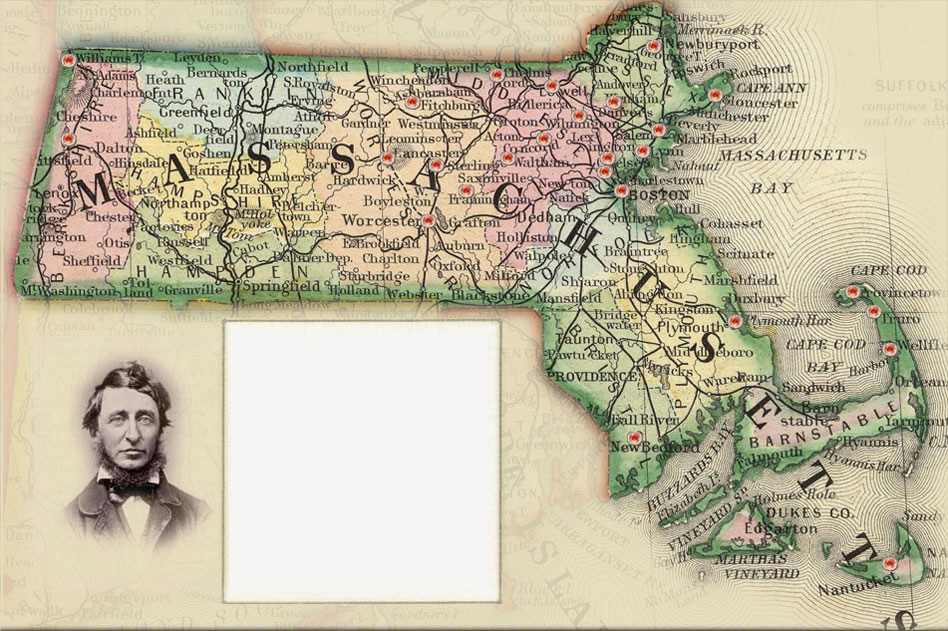

This site uses historical maps to organize and interpret documentary materials related to Thoreau's travels throughout Massachusetts. Clicking on the red map pins will open pages containing notes, images, quotes, and links to additional resources on Thoreau's contributions to American political, social, economic, and environmental thought. To view Thoreau's adventures in cartography, please click on Thoreau's Maps at the top of this page.

Learn More

-

34

641

-

63

484

-

73

537

-

83

703

-

90

601

-

90

401

-

104

567

-

118

646

-

138

630

-

145

595

-

167

593

-

127

57

-

142

376

-

180

612

-

209

416

-

127

531

-

145

497

-

151

425

-

179

454

-

279

840

-

298

861

-

308

722

-

425

621

-

552

878

-

50

60

Newburyport

Thoreau lectured on his excursions to Cape Cod at Market Hall in Newburyport on December 6, 1850. Read more...Chelmsford

The Thoreau family lived in Chelmsford from 1818-1821. Read more...Lowell

Lowell figured significantly in Thoreau's life, both as a site of lectures and a symbol of industrial expansion. Read more...Gloucester

Thoreau delivered "Economy-Illustrated by the Life of a Student," an early Walden lecture, here on December 20, 1848, Read more... South Danvers

Thoreau lectured on his travels on Cape Cod at the South Danvers Lyceum on February 18, 1850. Read more...

Fitchburg

Thoreau gave a lecture entitled "Walking, or the Wild" in Fitchburg on February 3, 1857. Read more...Bedford

Thoreau gave his lecture on "Wild Apples" at the Bedford Lyceum on February 14, 1860. Read more...Salem

Nathaniel Hawthorne arranged for Thoreau to lecture in Salem on two occasions, November 22, 1848 and February 28, 1849. Read more... Lynn

Thoreau delivered "Autumnal Tints" at Frazier Hall in Lynn on April 26, 1859. Read more...Medford

Thoreau read "Economy," a lecture that evolved into a chapter in Walden, in Medford on January 22, 1851. Read more...Cambridge

Thoreau attended Harvard College here from 1833 to 1837 and returned often to use the library. Read more...Pittsfield

In 1844, after a night on Mt. Greylock, Thoreau joined Ellery Channing here for a trip to the Catskills. Read more...Mt. Wachusett

After he hiked to Mt. Wachusett in July 1842, Thoreau turned his notes into "A Walk to Wachusett." Read more...Boston

Thoreau gave several lectures here between 1844 and 1859 including his defense of John Brown. Read more...Worcester

Thoreau lectured more frequently in Worcester than in any other place except Concord. Read more...Lincoln

Thoreau spent considerable time in Lincoln including six weeks living in a hut at Flint's Pond in 1837. Read more...Concord

Explore Thoreau's travels in Concord. Read more...Clinton

In 1851, Thoreau lectured here in response to an invitation from the Bigelow Charitable Mechanics Institute.Framingham

Thoreau delivered a fiery speech, "Slavery in Massachusetts, here on July 4, 1854. Read more...Provincetown

Thoreau took four trips to Cape Cod and recorded a wealth of entertaining observations. Read more...Truro

Thoreau lodged at the Highland Lighthouse during July 1855 while he studied the natural history of Cape Cod. Read more...Plymouth

Thoreau delivered his lecture on "Moonlight" here on October 8, 1854. Read more...New Bedford

Thoreau gave one of his most popular lectures, "What Shall It Profit," at the New Bedford Lyceum on December 26, 1854. Read more...Nantucket

Thoreau delivered "What Shall It Profit" at the Nantucket Lyceum on December 28, 1854. Read more...Mount Greylock

Thoreau made his first trip to Mt. Greylock in 1844. Read more...