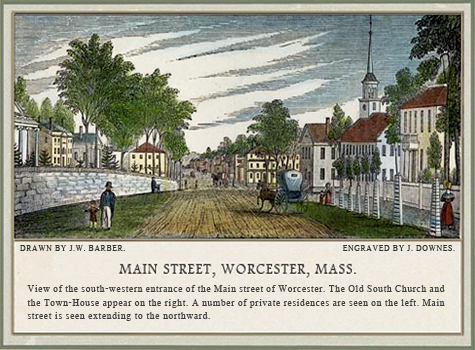

Visit the Worcester Historical Museum. Explore the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester. See what you can see at Arts Worcester. Visit the Worcester Art Museum. Explore Abby Kelley Foster's leading role in the struggle for equal rights for all in Worcester and the rest of the country. (Portrait by Charlotte Wharton). |

WorcesterThoreau lectured frequently in Worcester thanks in large part to a small band of admirers who promoted his participation in the city's vibrant literary and political scene. Of this group, his most ardent disciple was H.G.O. Blake, a graduate of Harvard Divinity School whose radical philosophical views steered him away from ministry into a job as a school teacher. Throughout the 1850's, Thoreau carried on an extensive correspondence with Blake, which eventually became the basis for informal gatherings at Blake's home in Worcester, where Thomas Wentworth Higginson and others would assemble to hear Blake read Thoreau's highly philosophical letters. While Blake can be described as Thoreau's first dedicated devotee, Higginson and Thoreau had much more in common as literary and political figures in mid-nineteenth-century Massachusetts. In his nature writings, for instance, Higginson frequently acknowledged Thoreau as a master observer, and he reported in an 1862 letter that his essay on "Snow," which was due to appear in the Atlantic, made him particularly proud because it had been praised by "Thoreau, the only critic whom I should regard as really formidable on such a subject." The parallels between Higginson and Thoreau as militant abolitionists are even more striking. Although Thoreau has sometimes been mistaken for a pacifist, there is no evidence that he ever strayed from his lifelong acceptance of forcible resistance as a legitimate response to tyrannical government. Higginson, who later came to be known as Col. Higginson in recognition of his distinguished service in the Civil War, took a similar position, especially after he moved from the relatively conservative town of Newburyport to Worcester, where he became a leading member of a sizable community of anti-slavery activists.

Until the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, abolitionists ranging from the pacifist William Lloyd Garrison to militants such as Theodore Parker agitated for the end of slavery mainly through sermons, petitions, and public meetings. However, after Massachusetts authorities actively assisted the rendition of fugitive slaves Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns to the South, the Garrisonian motto "No Union with Slaveholders!" took on new meaning for those who believed, in contrast to Garrison, that the violence inherent in slavery justified violent action against it. During the 1850's, these radicals, including Thoreau and Higginson, concluded that the time for forcible resistance to the authority embodied in the U.S. Constitution had come. In 1854, in the midst of what the newspapers described as the "Boston Slave Riot," Higginson acted on this conviction by attempting to smash a battering ram through the door of the courthouse where Burns was being held by federal marshals, a deed that Thoreau singled out in "Slavery in Massachusetts" as a heroic departure from what had become the norm of passivity. For Thoreau, the spinelessness exhibited by too many of his contemporaries provided yet more evidence of the corrupting effects of the state's ongoing duplicity in slavery. Thus he maintained that Massachusetts could only wake itself from the stupor of obedience to tyranny by cutting all ties with the federal government. "What should concern Massachusetts," he declared in his July 4th speech in Framingham, "is not the Nebraska Bill, nor the Fugitive Slave Bill, but her own slaveholding and servility. Let the State dissolve her union with the slaveholder. She may wriggle and hesitate, and ask leave to read the Constitution once more; but she can find no respectable law or precedent which sanctions the continuance of such a Union for an instant." In "Mourning in Massachusetts," a sermon preached in Worcester a few weeks earlier, Higginson likewise called for disunion, arguing that anything short of complete repudiation of the federal government would undermine any hope for the resurrection of freedom. "I do not expect to live to see [the Fugitive Slave Law] repealed by the votes of politicians at Washington. It can only be repealed by ourselves, upon the soil of Massachusetts. For one, I am glad to be deceived no longer. I am glad of the discovery—(no hasty thing, but gradually dawning upon me for ten years)—that I live under a despotism...my word of counsel to you is to learn this lesson thoroughly—a revolution is begun ! not a Reform, but a Revolution. If you take part in politics henceforward, let it be only to bring nearer the crisis which will either save or sunder this nation—or perhaps save in sundering." Thoreau and Higginson's shared militancy came the fore again when both championed John Brown's raid in Harper's Ferry in October 1859. Thoreau met Brown in 1857, when he visited Concord on a fundraising campaign to acquire arms for military action against pro-slavery forces in Kansas, and again in 1859, when he returned in search of additional financial support for his tiny army. During these years, Brown gained the admiration of Thoreau, Emerson, Alcott, and other Concordians, but thanks to Thoreau's friend and follower, Franklin Sanborn, his Concord host, Brown received much more tangible support from a group of Massachusetts militants who later came to be known as the "Secret Six." Higginson played a central role in this group, which also included, along with Sanborn, Samuel G. Howe, Gerrit Smith, George Luther Stearns, and Theodore Parker. Having already traveled to Kansas in 1856 to bring arms and supplies to anti-slavery forces, Higginson was well-positioned to arrange for the provision of pikes and rifles to Brown and his men. In the aftermath of the bloody foray into Harper's Ferry, which ended with Brown's capture and led to his execution on December 2, 1859, Higginson, like Thoreau and Sanborn, continued to hope that Brown's violent example would inspire the people of Massachusetts to take up arms against federal authorities, thereby provoking, if not a general insurrection, then at least consistent resistance to any law that upheld the rights of slave-holders. Having delivered his first public response to Brown's arrest in Concord on October 30, 1859, Thoreau wrote to Blake the next day to see if Higginson could arrange a repeat performance in Worcester. In the meantime, he accepted an urgent invitation from Charles Slack in Boston to replace Frederick Douglass, who had been scheduled to lecture at Tremont Temple on November 1, but had been chased into Canada by federal marshals on suspicion of involvement in Brown's raid. After extolling Brown's virtues before a large crowd in Boston, Thoreau gave essentially the same speech in Worcester on November 3. By that point, Higginson had already been taken to task in the New York press for having defended Brown's actions in a sermon on October 25 in which he reportedly asserted that the only regrettable aspect of the raid at Harper's Ferry was that it had not been successful and that, "nine out of ten of the Republicans at Worcester thought as he did!" Thoreau's remarks on Brown, which Bronson Alcott and others characterized as well-received in both Boston and Worcester, elicited similar condemnation in the Boston papers: "Mr. Thoreau, in his Fraternity Lecture, says there are at least a million free citizens of the United States who would have been glad if Old Brown's attempt to incite the slaves in Maryland and Virginia to murder defenceless women and children had succeeded! He blasphemously likened Brown to Christ...Thoreau would also "rather see the statue of John Brown in the State House yard than that of any other man he knew," (Applause)." Although his tribute to Brown was his last lecture in Worcester, his talks here in previous years included a three-part series of lectures on his life at Walden in 1849, and another three-part account of his travels on Cape Cod in 1850. He also uncharacteristically delivered two talks on the same subject in Worcester, speaking on "Walking, or the Wild" first in 1851, then again in 1857. |