Visit the Nantucket Atheneum. See the Great Point Light in the Coskata-Coatue Wildlife Refuge, managed by the Trustees of Reservations. Voyage to the Nantucket Whaling Museum. Visit the Egan Maritime Institute. Learn more at the Nantucket Historical Association. |

Nantucket"What Shall it Profit?," the lecture Thoreau delivered at the Nantucket Atheneum in December 1854, was substantially the same talk he gave elsewhere under the titles "Getting a Living" and "Life Misspent." However, we know the the work today as "Life without Principle," the title he assigned to it just before his death in 1862, when he prepared it for publication in the Atlantic Monthly. Of all of Thoreau's lectures, this was the closest he came to having a set piece ready whenever he was asked to speak. In all, he gave it at least nine times, delivering it last in Lowell in 1860. His decision to use this particular lecture to showcase his speaking talents was not based on the reception it received. In fact, immediately after he read it for the first time in Providence, Rhode Island on December 6, 1854, he reflected on his failure to engage his audience, wondering in a journal entry if he ought to focus on writing rather than lecturing as a means to convey his thoughts: "After lecturing twice this winter I feel that I am in danger of cheapening myself by trying to become a successful lecturer, i. e., to interest my audiences. I am disappointed to find that most that I am and value myself for is lost, or worse than lost, on my audience. I fail to get even the attention of the mass. I should suit them better if I suited myself less...I would rather that my audience come to me than that I should go to them, and so they be sifted; i. e., I would rather write books than lectures...To read to a promiscuous audience who are at your mercy the fine thoughts you solaced yourself with far away is as violent as to fatten geese by cramming, and in this case they do not get fatter." That his listeners or, in his analogy, "geese," seemed unappreciative is hardly surprising in view of the style and substance of the lecture. He began by complaining about the false notes sounded by speakers who try too hard to please their listeners, then announced his determination to avoid that fate no matter how boring his talk might be. He went on to address some of same themes that he had explored in Walden, excoriating the mindless materialism which was, in his view, poisoning mid-nineteenth-century American society.

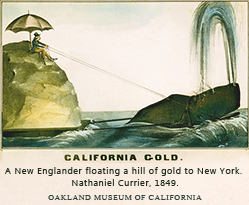

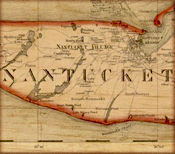

Although he did not spend much time on Nantucket, Thoreau took full advantage of the opportunity to explore the island. In keeping with his usual habits, he started by locating the best map of the area that he could find, in this case copying a map made by William Coffin (1834) that he found hanging in the lobby of the Ocean House Hotel. He spent the rest of the day touring with his host, Captain Edward Gardner, who pointed out interesting places such as the old house where Benjamin Franklin Folger, who was known as the island's most knowledgeable historian, lived in squalor among valuable antiquities which he refused to sell under any terms. Although audiences elsewhere seemed unmoved by Thoreau's critique of commercial schemes, the people of Nantucket apparently responded much more positively. Soon after he arrived home in Concord, he wrote to his New Bedford friend Daniel Ricketson, "In spite of all my experience, I persisted in reading to the Nantucket people the lecture which I read at New Bedford, and I found them to be the very audience for me." The Nantucketers' approval of Thoreau's condemnation of the chase after wealth makes sense in view of the economic decline that overtook the island in the 1850's as the shrinking whaling industry moved to deeper ports on the mainland, and the demand for whale oil gave way to a preference for cleaner-burning kerosene. During this period, many of the enterprising types who had once sought their fortunes at sea migrated west to join the quest for gold in California. Before his journey back to Concord, Thoreau stopped at the museum attached to the Athenaeum, where, as he noted in his journal, he saw a portrait of Abram Quary, the second to last member of the Wampanoags, once a flourishing Native American tribe on Nantucket. Quary died a few weeks before Thoreau's visit in 1854. Dorcas Honorable, the last Wampanoag woman, died in 1855.

|