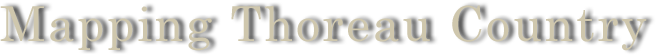

Visit Orchard House in Concord, Mass. Visit the Concord Museum (down the street from Orchard House.) Visit Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Mass. Explore Alcott holdings in Special Collections at the Concord Free Public Library. |

Orchard House

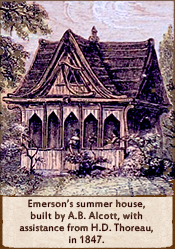

Having been forewarned about Alcott's handiwork, Emerson seems not to have minded the tottering result. He dubbed the house "Tumbledown Hall" upon his return to Concord, but that name gave way to "The Ruin" when it commenced to collapse over the course of a few seasons. Although Thoreau sometimes poked fun at Alcott's eccentricities, he consistently described him in glowing terms, devoting, for example, part of a chapter of Walden to extolling his older friend's virtues. Admiring Alcott's "hospitable intellect," Thoreau singled him out as "the sanest man" with the "fewest chrochets" of all he knew, and declared, "I think that he must be the man of the most faith of any alive." In line with this high opinion, Thoreau took a page from Alcott when he stopped paying his poll tax in 1842. Thoreau's refusal to pay taxes began partly as a protest against slavery, but served more broadly to express his objection to the government's failure to seek his explicit consent to its arrangements. Alcott's tax-resistance, which was, according to his philosophical devotee, Charles Lane, a rejection of "power and might" in favor of "peace and love," began in 1840. However, Alcott failed to provoke the State into action until January 1843, when a new tax collector in Concord began to enforce the law by demanding that Alcott pay the $1.50 due. Ultimately, after being carted off to jail, Alcott waited two hours to be clapped into a cell before it turned out that his tax had been paid by Samuel Hoar, a pillar of the Concord community. When Thoreau was arrested for non-payment of taxes in July 1846, and actually managed to spend a night in jail before someone, probably Maria Thoreau, his aunt, paid the bill, Emerson dismissed Thoreau's decision to break the law as both tasteless and foolish. In contrast, in January 1848, after hearing Thoreau's account of his incarceration in an early version of lecture that evolved into "Resistance to Civil Government" (1849), Alcott noted in his journal: "Heard Thoreau’s lecture before the Lyceum on the relation of the individual to the State — an admirable statement of the rights of the individual to self-government, and an attentive audience. His allusions to the Mexican War, to Mr. Hoar’s expulsion from Carolina, his own imprisonment in Concord Jail for refusal to pay his tax, Mr. Hoar’s payment of mine when taken to prison for a similar refusal, were all pertinent, well considered, and reasoned. I took great pleasure in this deed of Thoreau’s." Thoreau's fondness for Alcott did not incline him to join Fruitlands, the utopian community that Alcott co-founded with Lane in Harvard, Massachusetts in 1843. Like George Ripley, who had established Brook Farm in West Roxbury a few years earlier, Alcott and his fellow Transcendentalists dreamed of pursuing an entirely new and spiritually uplifting approach to daily life. Alcott was, however, neither resourceful nor disciplined enough to carry off the experiment. Having dragged Abigail May Alcott, his wife, and their children, including Louisa May Alcott—who would later become the breadwinner of the family through her best-selling writings—off to toil in his ostensible Eden, he was soon obliged to face the insanity of the project. Among the many factors involved in its demise, perhaps the most significant was the irrationality of its guiding principles, for example, the notion that vegetables which grow downward, such as potatoes, ought to be avoided due to their ignoble tendencies. While Emerson saw some limited value in both Brook Farm and Fruitlands as social experiments, Thoreau had no use for communal schemes. "As for these communities," he wrote in his journal in 1841, "I think I had rather keep bachelor's hall in hell than go to board in heaven. Do not think your virtue will be boarded with you...In heaven I hope to bake my own bread and clean my own linen. The tomb is the only boarding-house in which a hundred are served at once. In the catacombs we may dwell together and prop one another up without loss." |