Learn more about Thoreau at Cape Cod National Seashore. Explore the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Trail. Learn more about climate change on the Cape from the National Park Service. Join the Wellfleet Historical Society. |

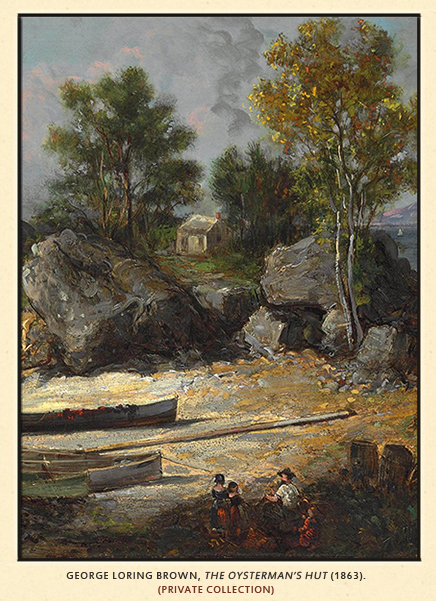

WellfleetCape Cod is often placed among Thoreau's nature writings because it includes so much information about the flora, fauna, and natural history of the region. In his opening chapter, however, he indicated that he would take a more ethnographical approach: "I did not see why I might not make a book on Cape Cod, as well as my neighbor on "Human Culture." It is but another name for the same thing, and hardly a sandier phase of it." In line with this reference to Human Culture, a collection of philosophical papers written by his friend and neighbor, Bronson Alcott, during the 1830's and 1840's, Cape Cod concentrated more, or at least more overtly and at length, on the customs and characteristics of the people he encountered than on plants, animals, birds, and topography, which take center stage in many of his works. A case in point is "The Wellfleet Oysterman," an entire chapter devoted to the conversations that he and his traveling companion, William Ellery Channing, carried on with an old man—later identified by locals as "Uncle Jack Newcomb"—during visits to Wellfleet in October 1849 and June 1850. Newcomb hardly needed drawing out, but Thoreau questioned him fairly methodically about the social, economic, and cultural development of the Cape. In the course of these interviews, he inquired about various aspects of the natural history of the area, but also prompted the eighty-eight-year old Newcomb to talk of his experience as a witness to the American Revolution, which elicited entertaining tidbits such as the oysterman's recollection of seeing General George Washington ride through the streets of Boston: "He was a r—a— ther large and portly-looking man, a manly and resolute-looking officer, with a pretty good leg as he sat on his horse." — "There, I'll tell you, this was the way with Washington." Then he jumped up again, and bowed gracefully to right and left, making show as if he were waving his hat. Said he, "That was Washington." In providing readers with amusing snatches of local culture, Thoreau was conforming to the conventions of travel writing, which was then evolving into a major segment of the literary market, both as a cause and as an effect of the growth of tourism as rail lines multiplied across New England. Indeed, the resemblance between Cape Cod, which is often described as Thoreau's most lighthearted work, and other mid-nineteenth-century travelogues suggests that he was trying very deliberately to tap into the rising demand for books and articles on newly accessible attractions such as Highland Light, where he lodged in 1855, thereby contributing to the transformation of the Cape from a collection of fishing villages into a major destination for tourists from around the world. Had he assessed the demand for works on travel, Thoreau would have immediately encountered Nathan Parker Willis, who became perhaps the most famous and highly paid magazine writer in the U.S. during the 1840's and 1850's. Willis wrote numerous works of poetry, but his literary success was due mainly to his essays on travel, some of which he contributed to the New York Mirror under the heading, "Pencillings by the Way," and others he collected into a single volume entitled Hurry-graphs; or, Sketches of Scenery, Celebrity, and Society in 1851. Hurry-graphs includes a series of letters from Cape Cod that might have inspired Thoreau, at least to the extent that Willis, like Thoreau, mixed bits of Cape history with stories of encounters with colorful locals, while also dispensing advice on how to travel and what to see. It is, however, the contrast between these two books that explains why Willis's work has largely been forgotten while Thoreau's has achieved landmark status. As much as Cape Cod might echo the conventions of nineteenth-century travel writing established by popular authors such as Willis, Thoreau made it plain that he was perfectly willing to defy expectations and discomfort his readers to make a larger point. After all, as entertaining as Cape Cod may be, it begins with a detailed and, some would say, gruesome description of a shipwreck, which is hardly a promising way of enticing tourists to take a trip to the sea.

|